Thomas never went to medical school, but he had a genius, a stunning dexterity. He might have been a great surgeon. Instead, he became a legend.

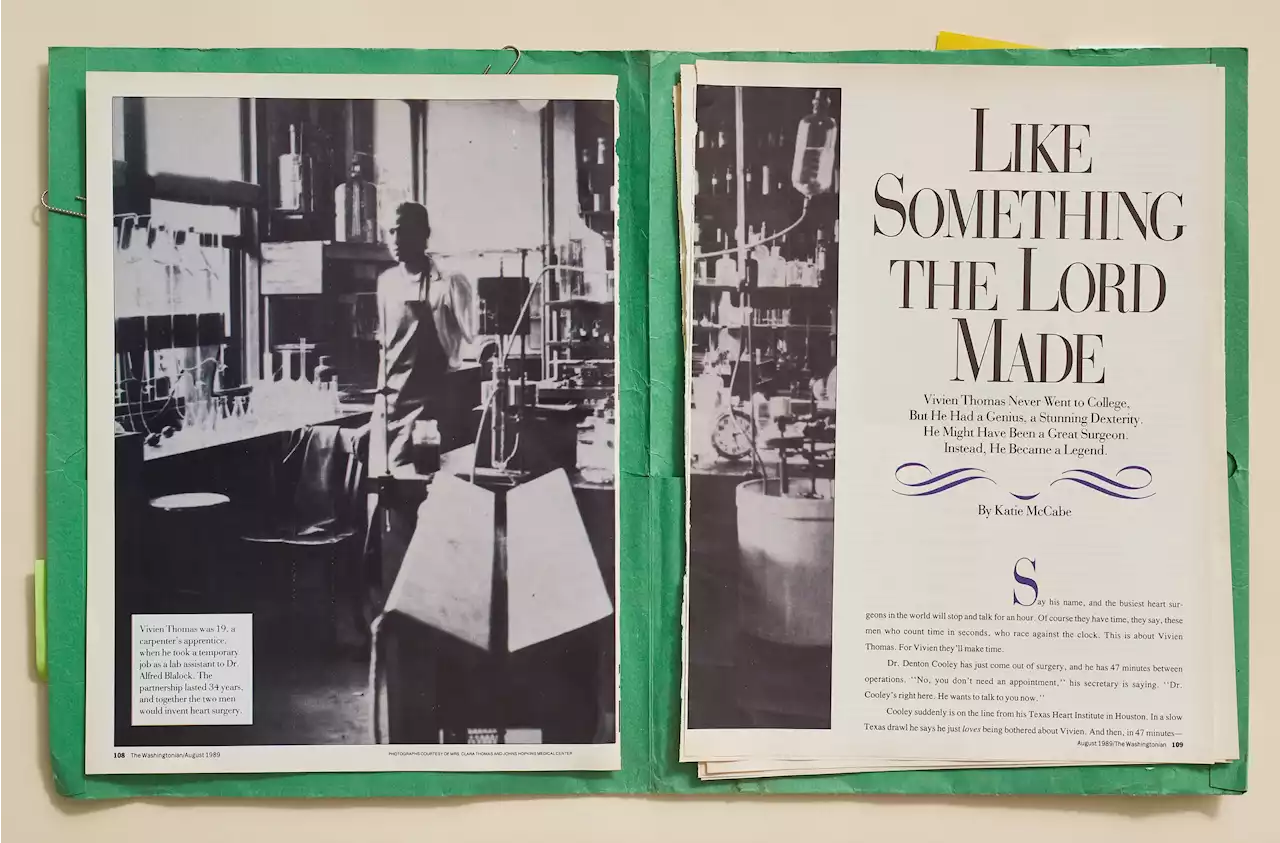

published what might be the most popular article in its history. “Like Something the Lord Made,” by Katie McCabe, tells of Vivien Thomas, an African American lab assistant to white surgeon Alfred Blalock from the 1930s to the ’60s. Thomas hadn’t gone to college, let alone medical school, but through their pioneering work together, the two men essentially invented cardiac surgery.

And could he operate. Even if you’d never seen surgery before, Cooley says, you could do it because Vivien made it look so simple. “You see,” explains Cooley, “it was Vivien who had worked it all out in the lab, in the canine heart, long before Dr. Blalock did Eileen, the first Blue Baby. There were no ‘cardiac experts’ then. That was the beginning.”

In 1930, Vivien Thomas was a nineteen-year-old carpenter’s apprentice with his sights set on Tennessee State College and then medical school. Blalock saw the same quality in Thomas, who exuded a no-nonsense attitude he had absorbed from his hard-working father. The well-spoken young man who sat on the lab stool politely responding to Blalock’s questions had never been in a laboratory before. Yet he was full of questions about the experiment in progress, eager to learn not just “what” but “why” and “how.” Instinctively, Blalock responded to that curiosity, describing his experiment as he showed Thomas around the lab.

From that day on, said Thomas, “neither one of us ever hesitated to tell the other, in a straightforward, man-to-man manner, what he thought or how he felt. . . . In retrospect, I think that incident set the stage for what I consider our mutual respect throughout the years.” But the young man who read chemistry and physiology textbooks by day and monitored experiments by night was doing more than surviving. For $12 a week, with no overtime pay for sixteen-hour days and no prospect of advancement or recognition, another man might have survived. Thomas excelled.

In his four years with Blalock, Thomas had assumed the role of a senior research fellow, with neither a PhD nor an MD. But as a black man doing highly technical research, he had never really fit into the system—a reality that became painfully clear when in a salary discussion with a black coworker, Thomas discovered that Vanderbilt classified him as a janitor.

Thomas had family obligations to consider, too. In December 1933, after a whirlwind courtship, he had married a young woman from Macon, Georgia, named Clara Flanders. Their first child, Olga Fay, was born the following year, and a second daughter, Theodosia, would arrive in 1938. The 1,000th Blue Baby operation was a happy occasion for Vivien Thomas and surgeon Alfred Blalock, who is pictured here with one of the babies in a Yousef Karsh portrait.

When they came to Hopkins, they brought with them solutions to the problems of shock that would save many wounded soldiers in World War II. They brought expertise in vascular surgery that would change medicine. And they brought five dogs, whose rebuilt hearts held the answer to a question no one yet had asked.

Thomas bristled. His father was a builder who had supported a family of seven. He meant to do at least as well for his own family. “I intend for my wife to take care of our children,” he told Blalock, “and I think I have the capability to let her do so—except I may have the wrong job.” Then, one morning in 1943, while Johns Hopkins and Vivien Thomas were still getting used to each other, someone asked a question that would change surgical history.In an extensive 1967 interview with medical historian Dr. Peter Olch, we meet the warm, wry Vivien Thomas who remains hidden behind the formal, scientific prose of his autobiography. He tells the Blue Baby story so matter-of-factly that you forget he’s outlining the beginning of cardiac surgery.

Off he went to the Pathology Museum, with its collection of congenitally defective hearts. For days, he went over the specimens—tiny hearts so deformed they didn’t even look like hearts. So complex was the four-part anomaly of Fallot’s tetralogy that Thomas thought it possible to reproduce only two of the defects, at most. “Nobody had fooled around with the heart before,” he says, “so we had no idea what trouble we might get into.

Overnight, the tetralogy operation moved from the lab to the operating room. Because there were no needles small enough to join the infant’s arteries, Thomas chopped off needles from the lab, held them steady with a clothespin at the eye end, and honed new points with an emery block. Suture silk for human arteries didn’t exist, so they made do with the silk Thomas had used in the lab—as well as the lab’s clamps, forceps, and right-angle nerve hook.

Nothing in the laboratory had prepared either one for what they saw when Blalock opened Eileen’s chest. Her blood vessels weren’t even half the size of those in the experimental animals used to develop the procedure, and they were full of the thick, dark, “blue” blood characteristic of cyanotic children. When Blalock exposed the pulmonary artery, then the subclavian—the two “pipes” he planned to reconnect— he turned to Thomas.

Finally, off came the bulldog clamps that had stopped the flow of blood during the operation. The anastomosis began to function, shunting the pure blue blood through the pulmonary artery into the lungs to be oxygenated. Underneath the sterile drapes, Eileen turned pink.Almost overnight, Operating Room 706 became “the heart room,” as dozens of Blue Babies and their parents came to Hopkins from all over the United States, then from abroad, spilling over into rooms on six floors of the hospital.

Then the perspiring Professor would complete the procedure, venting his tension with a whine so distinctive that a generation of surgeons still imitate it. “Must I operate all alone? Won’tplease help me?” he’d ask plaintively, stomping his soft white tennis shoes and looking around at the team standing ready to execute his every order.

“Dr. Blalock let us know in no uncertain terms, ‘When Vivien speaks, he’s speaking for me,’ ” remembers Dr. David Sabiston, who left Hopkins in 1964 to chair Duke University’s department of surgery. We revered him as we did our professor.” In any other hospital, Thomas’s functions as research consultant and surgical instruction might have been filled by as many as four specialists. Yet Thomas was always the patient teacher. And he never lost his sense of humor.

“He was strictly no-nonsense about the way he ran that lab,” Haller says. “Those dogs were treated like human patients.” To the black technicians he trained—twenty of them over three decades—he was “Mr. Thomas,” a man who represented what they themselves might become. Two of the twenty went on to medical school, but most were men like Thomas, with only high school diplomas and no prospect of further education. Thomas trained them and sent them out with the Old Hands, who tried to duplicate the Blalock-Thomas magic in their own labs.

Levi Watkins, Hopkins’s first black cardiac resident, shared a bond with Vivien Thomas that transcended their 34-year age difference. Watkins came to cherish the fatherly advice he received “from a man who knew what it was like to be the only one.” As close as Blalock was to his protégés, they moved on. It was Thomas who remained, the one constant. From the first, Thomas had seen the worst and the best of Blalock. Thomas knew the famous Blue Baby doctor the world could not see: a profoundly conscientious surgeon, devastated by patient mortality and keenly aware of his own limitations.

“It’s a chance I have to take,” he told Blalock. “I don’t know what will happen if I leave Hopkins, but I know what will happen if I stay. ”He made no salary demands, but simply announced his intention to leave, assuming that Blalock would be powerless against the system. As the hectic pace of the late ’40s slowed in the early ’50s, the hurried noon visits and evening phone conversations gave way to long, relaxed exchanges through the open door between lab and office.

“You were lucky to have hit the jackpot twice,” Thomas answered, remembering that the good old days were, more often than not, sixteen-hour days. Besides, it was Blalock, 60 years old, recently widowed and in failing health, who was feeling old, not Thomas, then only 49. Perhaps Blalock was remembering what it had been like when he was 30 and Thomas 19, juggling a dozen research projects, working into the night, trying to “find out what happens.

Weeks after the last research project had been ended, Blalock and Thomas made one final trip to the “heart room”—not the Room 706 of the early days, but a glistening new surgical suite Blalock had built with money from the now well-filled coffers of the department of surgery. The Old Hunterian, too, had been replaced by a state-of-the-art research facility.

“Seeing that he was unable to stand erect,” Thomas recalled later, “I asked if he wanted me to accompany him to the front of the hospital. His reply was, ‘No, don’t.’ I watched as with an almost 45-degree stoop and obviously in pain, he slowly disappeared through the exit.”During his final illness Blalock said to a colleague: “I should have found a way to send Vivien to medical school.

It was the admiration and affection of the men he trained that Thomas valued most. Year after year, the Old Hands came back to visit, one at a time, and on February 27, 1971, all at once. From across the country they arrived, packing the Hopkins auditorium to present the portrait they had commissioned of “our colleague, Vivien Thomas.”

Five years later, the recognition of Vivien Thomas’s achievements was complete when Johns Hopkins awarded him an honorary doctorate and an appointment to the medical-school faculty.Presentation of a Portrait: The Story of a Life It is not Thomas’s diploma that guests first see when they visit the family’s home, but row upon row of children’s and grandchildren’s graduation pictures. Lining the walls of the living room, two generations in caps and gowns tell the story of the degrees that mattered more to Thomas than the one he gave up and the one he finally received.

That was what he and Thomas talked about the day they met in the hospital cafeteria, a few weeks after Watkins had come to Hopkins as an intern in 1971. “You’re the man in the picture,” he had said. And Thomas had smiled and invited him up to his office.to get your picture on the wall?’ ” says Watkins of his first meeting with a man who was for fourteen years “a colleague, a counselor, a friend.”

Malaysia Latest News, Malaysia Headlines

Similar News:You can also read news stories similar to this one that we have collected from other news sources.

MAP: State of the Union Road Closures - WashingtonianPolice will close roads around the Capitol in stages beginning at 6:30 AM.

MAP: State of the Union Road Closures - WashingtonianPolice will close roads around the Capitol in stages beginning at 6:30 AM.

Read more »

Dan Snyder Is Selling His Potomac Estate for $49 Million - WashingtonianIf it sells at that price, it will be the biggest residential real estate sale ever in the DC area.

Dan Snyder Is Selling His Potomac Estate for $49 Million - WashingtonianIf it sells at that price, it will be the biggest residential real estate sale ever in the DC area.

Read more »

Clippers surge late, outlast Cam Thomas, NetsPaul George scores 29 points, Kawhi Leonard has 24 points and six assists and the Clippers outscore Brooklyn 25-9 over the final 6:20 to overcome Thomas’ career-high 47 points and wrap their six-ga…

Clippers surge late, outlast Cam Thomas, NetsPaul George scores 29 points, Kawhi Leonard has 24 points and six assists and the Clippers outscore Brooklyn 25-9 over the final 6:20 to overcome Thomas’ career-high 47 points and wrap their six-ga…

Read more »

Nets waste Cam Thomas’ 47 points in loss to Clippers to start post-Kyrie Irving eraThe Nets’ first game of the post-Kyrie Irving era ended with a shorthanded defeat, a 124-116 loss to the Clippers before 16,981 at Barclays Center.

Nets waste Cam Thomas’ 47 points in loss to Clippers to start post-Kyrie Irving eraThe Nets’ first game of the post-Kyrie Irving era ended with a shorthanded defeat, a 124-116 loss to the Clippers before 16,981 at Barclays Center.

Read more »

Cam Thomas drops 47 points, but Nets fall to Paul George and ClippersCam Thomas scored a career-high 47 points, but it wasn't enough as the Nets fell to the Clippers 124-116 on Monday night. NetsWorld

Cam Thomas drops 47 points, but Nets fall to Paul George and ClippersCam Thomas scored a career-high 47 points, but it wasn't enough as the Nets fell to the Clippers 124-116 on Monday night. NetsWorld

Read more »