“It took me most of my 30s to adjust to being in my 30s,” Nancy Franklin wrote, in 1995, “to come to terms with the knowledge that the inability to make decisions had had a decisive effect on my life.” NewYorkerArchive

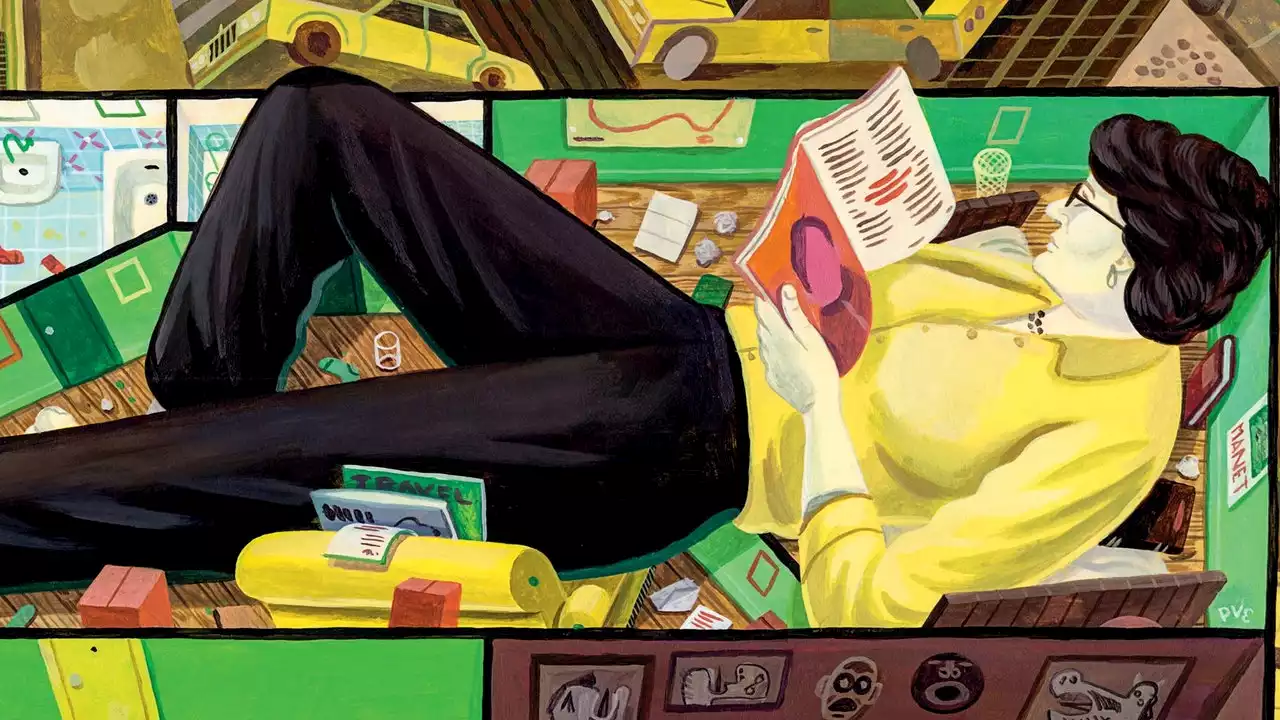

After a few years, I thought from time to time about moving, and for the past five or six I thought about it constantly. But I had a sense of pride about my stability, and believed that if I stayed in the same apartment long enough the time I’d spent there would acquire weight and meaning. I would have a history, and I would be able to look back on it and see that it all made sense. I would stand out in people’s address books among all the other addresses that had been crossed out or erased.

I dream about my apartment all the time, the same two dreams over and over. One is a bad dream: I wake up and realize that I have no front door, or that the door doesn’t lock, or that the door is a Dutch door, and the top part doesn’t lock, so anyone can get in. Nothing terrible actually happens to me, but I have the terrible awareness that I’ve never been safe, that I’ve ignored threats and warnings, that I haven’t lived right.

When I say that I’ve always hated my next-door neighbors and that they’ve ruined my life, I mean it as a tribute—an acknowledgment that my outsized feelings about the noise that comes through the wall have more to do with me than with any unneighborly activity on their part. But when you live alone and yet don’t have the one advantage that’s supposed to come with the territory—real, true privacy—you end up not so much living alone as feeling alone.