Subtle signals from black hole mergers might confirm the existence of “Hawking radiation”—and gravitational-wave detectors may have already seen them.

In 1974 Stephen Hawking theorized that black holes are not black but slowly emit thermal radiation. Hawking’s prediction shook physics to its core because it implied that black holes cannot last forever and that they instead, over eons, evaporate into nothingness—except, however, for one small problem: there is simply no way to see such faint radiation. But if this “Hawking radiation” could somehow be stimulated and amplified, it might be detectable, according to some astrophysicists.

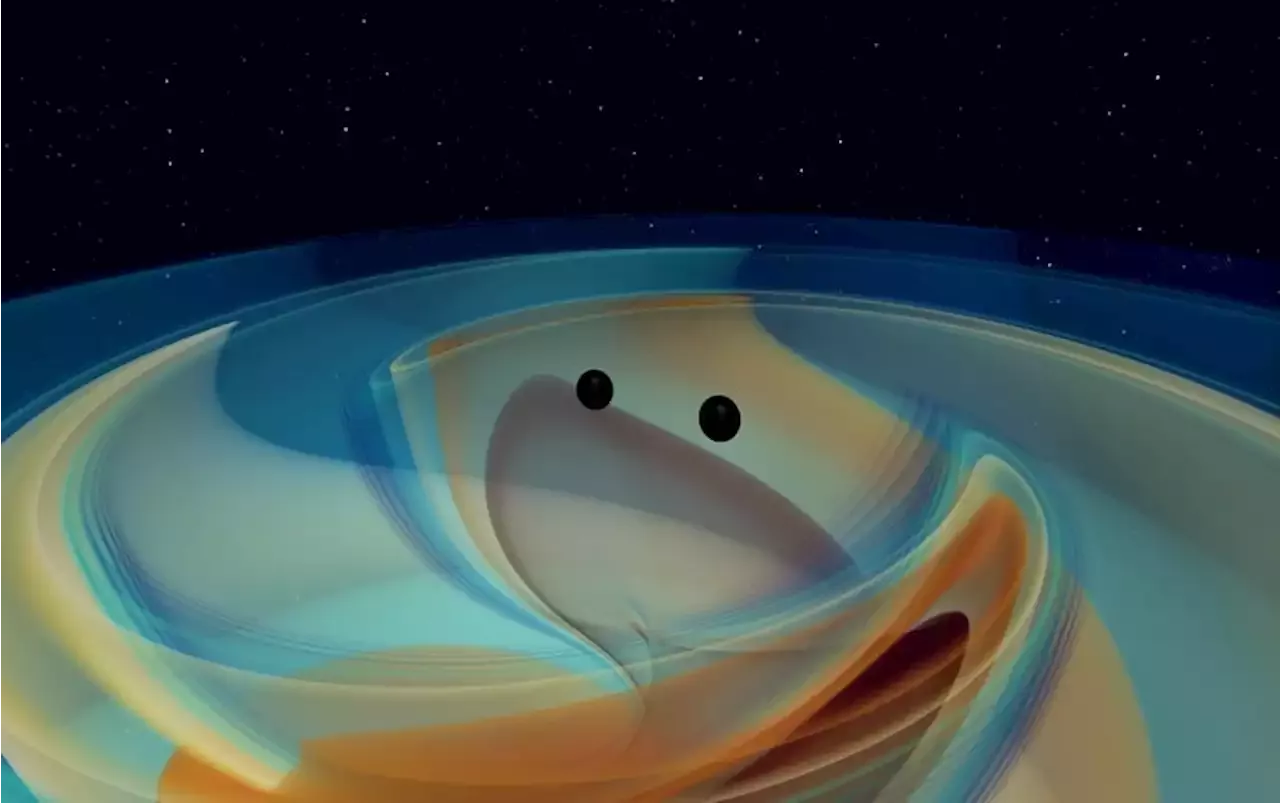

The gravitational waves from this event, named GW190521, not only rippled out to eventually interact with LIGO’s and Virgo’s detectors on Earth; they also washed over the remnant black hole produced by the initial collision. What happened next depends on your view of black hole physics. If black holes are described entirely by Einstein’s general theory of relativity, then they have an event horizon—a one-way boundary that anything can fall into but from which nothing can escape.

The principle is somewhat similar to what occurs during stimulated emission of radiation in atoms. In this process, photons of light hit “excited” electrons in atoms, causing the electrons to drop to lower energy levels while spitting out photons that have the same wavelength as the incident photons. In certain situations, this stimulated emission can far exceed the spontaneous “background” emission of radiation .

The researchers’ statistical analysis gives 0.5 percent odds that the putative signal is instead merely noise. Normally, for physicists to claim a discovery, the odds of a false alarm have to be lower than one in a million. Consequently, Pani, who was not part of the team, is circumspect. “The statistical evidence they have is ... definitely too low to claim a measurement,” he says.